Ontario Lot Grading and Drainage Requirements

If you’ve ever wondered why municipalities obsess over “swales” and “finished grade,” here’s the reason: water is extremely motivated. It will find the lowest point on your lot, invite all its friends, and then politely introduce itself to your basement. Lot grading is the easiest, cheapest way to keep that from happening.

This guide explains Ontario lot grading and drainage requirements in plain English for 2026: what the Ontario Building Code expects, why municipalities require grading plans, when you’ll see deposits and certificates, how conservation authorities can get involved, and the step-by-step process that keeps your new home dry and your neighbours friendly.

- Finished grade: the final elevations of soil around the house and yard.

- Surface drainage: directing rain and snowmelt so it won’t pond beside the foundation or flow onto neighbours.

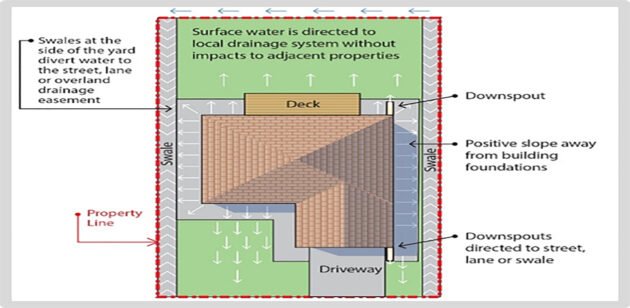

- Swales: shallow “channels” that guide water to a safe outlet.

- Low points + catch basins: where water is collected (if required) and routed to an approved outlet.

- Downspout discharge: where roof water goes (a big deal that people treat like a small deal).

Ontario municipalities are getting stricter on drainage because infill is tighter, lots are smaller, extreme rain events happen, and nobody wants stormwater disputes turning into “neighbourhood drama.”

Expect grading and drainage to be reviewed as part of building permits (especially in serviced areas, infill, subdivisions, and near regulated lands).

1) The Ontario-wide rule: “Don’t let water accumulate at or near the building”

While lot grading is heavily “municipal,” Ontario does have a core code expectation that influences everything: the building should be located or the site graded so water won’t accumulate at or near the building and won’t adversely affect adjacent properties. That’s the spirit of Ontario Building Code surface drainage requirements, and it’s the reason inspectors and plan reviewers care about grades.

Pair that with foundation drainage requirements (think perimeter drainage / weeping tile where needed), and you get the two-layer defence for basements and foundations: surface water stays away, and subsurface water has a controlled path. When both layers are done properly, basements behave. When either layer is ignored, water does what water does—shows up uninvited.

The key concept is simple: don’t create low spots near the foundation where water can pond. Grade should direct water away from the building and away from neighbouring properties.

Where required, drainage is provided at the bottom of foundation walls that contain the building interior. This supports water management around below-grade spaces.

2) Why municipalities take grading seriously (and why it’s not “just landscaping”)

Municipalities aren’t trying to micromanage your yard décor. They’re trying to prevent: basement seepage claims, sidewalk icing, flooded neighbour yards, overloaded storm systems, and erosion into waterways. A grading plan is basically the municipality saying, “Show us your water plan.”

In many Ontario communities, grading and drainage review is tied to: building permits, site alteration permits, site plan approval, and subdivision agreements. That’s why you’ll hear terms like “approved lot grading plan,” “as-built grading,” “certificate of finished grading,” and “grading security.”

In subdivisions, a master grading plan is part of engineering design. Your individual lot plan typically must match the subdivision’s approved drainage concept (swales, outlets, elevations).

Infill homes can trigger more grading review because drainage changes can affect adjacent properties immediately. Some municipalities handle infill grading through site alteration permits and security deposits.

3) The two big deliverables: the grading plan and the certificate

If you’re building a new home in Ontario, you’ll usually run into these two documents in some form:

This is the “what we intend to build” drawing. It shows proposed elevations, slopes, swales, high/low points, and where water goes. Depending on the municipality and project type, it may need to be prepared or stamped by a qualified professional (often a P.Eng or OLS).

This is the “we built what we promised” confirmation after construction. Many municipalities require a final certificate before releasing grading securities or closing files.

You can see this “plan → certificate” approach in many Ontario municipalities: some require a final “lot grading certificate” for new builds or infill, and some tie grading to deposits and permit closeout. The specific paperwork varies, but the structure is consistent: design it, build it, prove it.

4) Deposits, securities, and the myth of “free money”

Grading deposits (or securities) are common in Ontario. They exist for one reason: to make sure the final grading is actually completed as approved, and not “mostly done” with a few mystery low spots left behind. The deposit is typically held until grading is certified and the municipality is satisfied.

Deposit amounts vary widely. Some municipalities require deposits as part of the building permit process (often a few thousand dollars per lot), and may deduct review fees from that deposit. The numbers change by municipality, project type, and whether you’re in a subdivision or infill scenario. The important thing is to budget it and plan for the release steps.

5) Conservation authorities and regulated areas: when grading becomes “development”

If your lot is near wetlands, watercourses, valley/stream corridors, shorelines, or hazardous lands, you may be inside a regulated area. In that case, grading, filling, or altering the site can require permission under conservation authority permitting rules. This is where homeowners get surprised: “But I’m just shaping my yard” can still count as regulated activity if it’s in the regulated zone.

In 2024, Ontario moved to a new regulation framework for conservation authority permissions (Ontario Regulation 41/24), and local authorities now administer permits under that regulation. Practically, that means: check early whether you’re regulated, and get written confirmation if a permit is not required.

Contact your local conservation authority, confirm if your property is within the regulated area, and ask what activities require permission (grading, placing fill, altering drainage routes, etc.).

Conservation authority clearance can be “Applicable Law” for building permits. If it applies, your permit can stall until the clearance is provided.

6) The grading blueprint for new homes in Ontario (the step-by-step version)

Here’s the workflow I recommend for a new home lot in Ontario—whether you’re in a subdivision, rural lot, or infill project. It keeps your approvals clean and prevents costly rework.

7) Common grading mistakes (the greatest hits… unfortunately)

If you want to avoid basement moisture, neighbour complaints, and regrading costs, avoid these classics:

- Negative grade: soil slopes toward the foundation instead of away. Water collects at the wall and finds a way in.

- Swales filled in “because they look weird”: swales are often required to carry water off the lot safely.

- Downspouts dumping at the foundation: roof water is a huge volume in a storm. Put it where it belongs.

- Hardscape added later without a drainage plan: patios/driveways can redirect water toward the house or onto neighbours.

- Topsoil too high at siding: landscaping that bridges clearance zones can cause moisture and durability problems.

- Window wells without drainage: a window well can become a bucket. Buckets fill.

8) How municipalities typically review grading (what they’re actually checking)

Grading reviews vary, but municipal reviewers usually look for the same core logic:

| Reviewer focus | What it means in real life | How you avoid problems |

|---|---|---|

| Water won’t pond at the building | Finished grade slopes away so water can’t sit by the foundation. | Set elevations early; rough grade after backfill; keep low points away from walls. |

| Neighbouring properties aren’t harmed | No dumping water onto adjacent lots or creating new flooding paths. | Follow subdivision swales/outlets; confirm lot line drainage intent. |

| Safe outlet is provided | Swales/catch basins route water to an approved municipal or engineered outlet. | Don’t invent routes; tie into the approved drainage concept. |

| Regulated areas respected | No grading/fill within regulated hazard zones without permission. | Check conservation authority mapping and get written clearance. |

9) New homeowner “field checklist” for grading day

When you’re walking the site (or supervising your contractor), use this easy checklist:

- Grade slopes away from the foundation on all sides.

- No low “bowls” beside window wells, stairs, or downspouts.

- Topsoil height respects clearances at the wall (don’t bury materials that shouldn’t be buried).

- Downspouts discharge away from the foundation and toward swales/outlets.

- Swales are shaped and continuous (no random berms blocking them).

- Water has a clear path to the approved outlet.

- Driveway and patios don’t send water toward the house or neighbour.

- Any catch basin/grate is at the low point and not buried.

10) Final thoughts: grading is boring… until it’s expensive

Lot grading is one of those construction topics that feels unglamorous—until you’re dealing with water in a basement, ice on walkways, or a neighbour asking why your runoff now visits their backyard every time it rains. The good news is: done correctly, grading is simple, repeatable, and usually far cheaper than interior water repairs.

If you’re planning a new home, treat grading as a “design item,” not a “landscaping item.” That means: build the grading plan into your process early, set elevations correctly, rough grade during construction, and finish with certification if required. It’s the clean, professional way to close a build.

Friendly disclaimer: This is practical education, not engineering or legal advice. Ontario requirements vary by municipality, subdivision agreement, site conditions, and whether regulated lands are involved. Always confirm the specific grading and drainage submission requirements with your local municipality and (if applicable) your local conservation authority.

Scroll sideways to see more. Cards stay the same height (no messy uneven rows).