Radon rough-in Ontario

Are Radon Rough-Ins Now Required in New Ontario Homes? (Yes—Here’s What That Means)

You’ve probably heard it in passing: “Ontario now needs a radon rough-in.” And then—because construction loves vague phrases— everyone nods like they know exactly what that includes.

Let’s make it crystal clear. Radon rough-in Ontario requirements are now a real, province-wide code expectation for new homes. It doesn’t mean every house needs a fan installed on day one, but it does mean the home must be built so radon can be dealt with quickly if testing shows high levels later.

First: what is radon (and why Ontario finally got serious about it)?

Radon is a naturally occurring radioactive gas that comes from the ground. It can enter homes through cracks, joints, sump pits, slab penetrations, and tiny gaps you can’t even see—but your basement can “see them” just fine. The problem isn’t radon existing (it’s everywhere at some level). The problem is when it accumulates indoors and you breathe it over long periods.

Health Canada’s guideline is 200 Bq/m³. If a long-term test shows levels above that, the recommendation is to reduce them. That’s why modern codes focus on two things: blocking soil gas entry and making future mitigation easy.

Homeowner translation: You can’t “guess” radon. You test for it. If it’s high, you fix it. And the new code is basically saying, “Let’s not make fixing it a demolition project.”

So… are radon mitigation rough-ins required in Ontario now?

For new homes, the practical answer is yes: the 2024 Ontario Building Code (in effect January 1, 2025) strengthened radon and soil gas requirements and requires a rough-in for radon extraction for Part 9 residential occupancies (the category most new houses fall under). You’ll also see municipalities calling for a dedicated radon rough-in inspection as part of the build sequence—often before the slab is poured.

If you want a broader overview of what else changed in the same wave of updates (and why building departments may be more detail-focused now), see our breakdown: Ontario Building Code Changes for 2025.

Important nuance: “Required rough-in” does not automatically mean “active fan required at occupancy.” A rough-in is the code’s way of saying: build it so it can be activated later without tearing your home apart.

What exactly is a “radon rough-in”?

Think of radon mitigation like a plumbing vent—except instead of venting sewer gas, we’re venting soil gas from under the slab. A typical radon system is called a subfloor depressurization system (sometimes called SSD). When active, it uses a fan to pull air from beneath the slab and vent it safely outdoors. When passive (rough-in only), the groundwork is there so the system can be completed later.

The rough-in usually includes 3 core ingredients

Typically a continuous membrane (often 6 mil poly or equivalent approach), with sealed penetrations and continuity details. This is where workmanship matters: one sloppy cut can defeat a whole sheet.

Usually a 100 mm (4″) pipe stubbed from below the slab to a location where it can be extended and vented. The goal is to create a clear future pathway for suction under the slab.

The rough-in must be positioned so the system can be completed later—without ugly routing or “we’ll just box it in” compromises that homeowners hate and inspectors love to question.

The big idea is simple: don’t wait until after move-in to make the house radon-ready. If you ever need to activate mitigation, you want a clean path: connect fan + connect vent + verify performance. Not “break concrete, move finishes, and turn your basement into a dust factory.”

Does this apply to every new home?

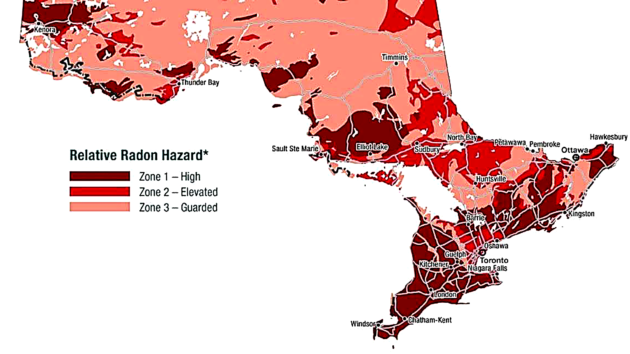

Most new ground-contact homes fall into the requirement. If you have a basement, crawl space, or slab-on-grade, you’re in the zone where soil gas control matters. Even when radon levels vary by region, the code approach is essentially: treat radon readiness as a standard baseline, not a “maybe” upgrade.

The only time this gets more nuanced is when you’re dealing with unusual occupancy types, additions, or special foundation designs. But for typical new detached homes, the safest assumption is: your building department expects a radon rough-in.

My advice as a builder: Don’t fight this requirement. It’s cheap insurance while the slab is open. Fighting it later is like arguing with gravity—eventually gravity wins, and you pay for the lesson.

What inspectors look for (and where builders get nailed)

The radon rough-in inspection is often tied to the “partial air barrier” inspection—because the code intent is about preventing soil gas entry. Inspectors commonly focus on continuity, sealing, and obvious weak points.

Common “pass” ingredients

- Barrier is continuous (no random gaps or torn sections).

- Penetrations are sealed (plumbing, posts, sleeves, etc.).

- Rough-in pipe location matches plans and is accessible for future work.

- Slab edge / wall transitions are handled properly (where many leaks happen).

Inspectors like boring. Boring means predictable and compliant.

Common “fail” triggers

- Barrier punctured and “we’ll tape it later” (later never comes).

- Unsealed penetrations (especially at odd angles).

- Pipe rough-in buried, inaccessible, or placed where future fan/venting is unrealistic.

- Slab prep rushed: wrinkles, tears, gaps at edges, messy overlaps.

A radon rough-in fail usually isn’t complicated. It’s sloppy.

Does a radon rough-in guarantee low radon?

No—and this is an important expectation check. A rough-in doesn’t guarantee a low radon reading any more than a seatbelt guarantees nobody gets hurt. It’s a safety system. It reduces risk and makes the next step easy if you need it.

The only way to know your home’s radon level is to test (ideally with a long-term test). If the level is above the guideline, you mitigate. Most mitigation systems are straightforward when the rough-in is done correctly.

Testing mistake: doing a short test, seeing a low number, and declaring victory forever. Radon varies seasonally, weather-to-weather, and house-to-house. Long-term testing is the real signal.

How Tarion fits into this (yes, it matters)

Here’s where Ontario is actually a bit unique. In Ontario, Tarion’s statutory warranty includes radon remediation coverage for qualifying homes within the warranty period, provided your testing meets the program requirements. Tarion has a plain-language overview here: Tarion: How your new home warranty protects you against the dangers of radon gas .

This doesn’t mean homeowners should ignore radon until something goes wrong. It means: the system recognizes radon as a legitimate health and building performance issue, and there’s a structured path if you discover elevated levels in a newer home.

Builder tip: A clean rough-in plus clean documentation makes everyone’s life easier later—homeowner, builder, and warranty process.

Where does radon enter a house?

If you want to understand why “a few small gaps” matter, here’s the usual radon entry route map. The house is slightly negative pressure at times (stack effect, exhaust fans, wind), and soil gas wants in. It doesn’t need a big hole—just a pathway.

- Cracks and cold joints in slabs and foundation walls

- Sump pits and perimeter drains (if not sealed properly)

- Plumbing penetrations through slab and walls

- Floor drains, cleanouts, and utility sleeves

- Crawl space soil exposed or poorly sealed ground cover

This is also why good foundation design and detailing matters. Your envelope starts below grade. If you’re pricing foundation options and want to understand cost drivers, this is useful: ICF Foundation Cost.

How to test for radon (the homeowner-friendly version)

The best practice is a long-term test (often 3 months or more) placed in the lowest lived-in level of the home (often the basement, if finished or used). You don’t run around opening windows to “help” the test. You live normally. The goal is to measure real conditions.

Health Canada explains the guideline and measurement approach here: Health Canada: Radon guideline (200 Bq/m³) .

What if the test is high?

If your result is above the guideline, you don’t panic. You mitigate. In most cases, active sub-slab depressurization is the standard method: add a fan to the rough-in, vent to the exterior in a compliant way, and confirm that levels drop.

If your builder did a proper rough-in, mitigation is usually clean and efficient—no demolition drama required. And if you’re building high-performance foundations (including ICF), planning the rough-in routing early keeps your mechanical room neat and future-proof. For builder-grade ICF + below-grade best practices, see: ICFPRO.ca.

How this affects permits, scheduling, and your build timeline

Practically, the radon rough-in becomes one more item that must be ready before the slab is poured (or before certain stages are closed in). That means it’s not a “later” task—it’s a coordination task between excavation, plumbing, slab prep, and whoever is responsible for the soil gas barrier.

If you’re a homeowner acting as your own GC, or you’re trying to understand how the permit process ties to inspections, read: How to Get a Building Permit in Ontario. This is exactly the kind of “small detail” that becomes a failed inspection if nobody owns it.

Schedule reality: the slab pour date is not the day to remember radon. The slab pour date is the day to be finished and ready.

Bottom line: what homeowners should ask their builder

Here are the three questions that keep things simple and prevent confusion:

You want a location that’s accessible and logical—not hidden behind a finished wall with no path to an exhaust point.

Continuity matters. A barrier is only as good as the weakest penetration.

“We’ll call the City” isn’t a plan. A booked inspection is a plan.

Final thought: This update is a win for homeowners. A radon rough-in costs very little during construction and can save a lot of cost and disruption later. The key is not whether you “like” the rule—the key is making sure it’s done cleanly so you actually benefit from it.

Disclaimer: This article is educational and practical. Municipal requirements and interpretation can vary. Confirm inspection and documentation requirements with your local building department and qualified professionals.